The Road to Mastery

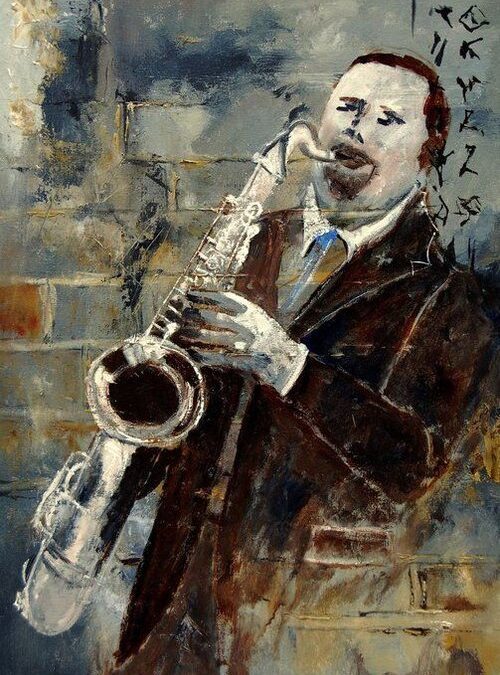

The smooth syncopated sounds from the saxophone section grabbed my attention with the force of a hammer blow to the temple. Tuxedo Junction played on the juke box. I couldn’t get enough. I used every quarter I had to feed the music machine and searched for change of my few dollar bills.

At twelve years old, the old sounds of the forties and fifties were unknown to me until this moment. At ten, I knew and loved every rock and roll tune that came out. Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti propelled me to buy my first 45 rpm record. Johnny Horton’s Battle of New Orleans followed. Then I heard my all-time favorite, Fats Domino, and his classics, Blueberry Hill and I’m Walkin’.

The rock songs catered to my unsophisticated music appreciation. Glen Miller’s Tuxedo Junction moved me in a different way. The beauty of harmony in sound and the restrained power of the tempo held me, and I didn’t want to let go.

My obsession with the tenor saxophone began. I wanted to play like them. The motivation was strong, sincere, and honest.

I had my previous encounters with piano lessons and tap dancing—both at the direction of my mother. She loved the piano and wanted me to love it too. The problem was I liked the piano, enough to give it a go for three years, but not enough to overcome my desire to be with friends after school, at the expense of practicing. The piano teacher, Mrs.

Glassel, let me know in no uncertain terms by her continuous sighing during our weekly lesson that the end was near.

The tap dancing was different. My mother wanted me to acquire social grace. I became light on my feet and could produce a passable time step when called upon. The venture lasted until the big recital. After the finale, I gave up my Capezios.

The saxophone was different. My mother didn’t ask me to play the instrument. I brought the idea to her. “We’ve spent enough on lessons.” She had a point about the money but missed the point about desire. So I talked with my father. He seemed to understand, and he liked the big band music. “Okay, Howard. If you earn the money for a saxophone, we’ll pay for the lessons.”

I had a chance to quench my yearning. The steam laundry in town needed someone to sweep the two-story building at the end of the work day. Dust and lint buildup posed a fire hazard. My job entailed throwing green-colored powder on the floor and sweeping it up with the lint and dust in it. I lost five pounds every night in the hot building. The thought of the saxophone drove me on. At summer’s end, I earned one-hundred fifty dollars—enough to buy a used saxophone. My father found one in a pawn shop and brought it home.

A man named Ray Sciarra lived in my Catskill Mountain town. He delivered the mail to rural post boxes and gave music lessons. A big band musician who gave up touring to start a family, he played the alto saxophone and clarinet. When I first met him, he wanted me to hear a professional sound. The music floating out from that alto sax was marvelous. This man could take me where I wanted to go.

Whatever he told me, I wanted to do. He knew the secrets I wanted to learn. I practiced continuously. As I progressed, he invited me, on occasion, to join his four-piece band that played at firemen’s suppers, fundraisers for the volunteer departments.

During one afternoon lesson, Ray opened the Glen Miller songbook to April in Paris. “Howard, I want you to take the lead.”

Past puberty, I understood the romantic feeling the song embodied and what the words would mean to someone in love. I summoned the emotion and moved it through the horn.

When we finished, Ray paused and looked at me. “Howard, I couldn’t have played that better myself.”

That moment has stayed with me to this day. A man I respected and admired, a professional musician at the top of his artistry told me I performed at his level. For three-and-a-half minutes, I attained mastery.

Ray not only taught me to play the tenor saxophone, he gave me a lesson in how to succeed. Although he is long gone from this earth, he still lives in my memory and heart. God bless you, Ray.