Ansel vs Howard: The Battle of Yosemite

A Short Story by Howard Feigenbaum

Ansel vs Howard: The Battle of Yosemite

Ansel vs Howard: The Battle of Yosemite

Twenty-two years ago, an April family vacation to Yosemite, the land carved by glaciers, set me to thinking. As I packed, my mind settled on a discomforting thought. How could my puny, predictable thirty-five millimeter photographs ever compare to Ansel Adams’ majestic prints? I wanted to avoid joining the multitude, cameras slung around their necks, who would have done better buying postcards featuring the master’s work.

Who would an amateur nature photographer admire more than Ansel Adams? Nobody. His photographs are synonymous with Yosemite National Park. Ansel’s large format view camera, his patience in waiting for the perfect moment to shoot the scene and his skill in the darkroom combined to portray the beauty and drama of Yosemite.

Sure, he had a proven system for composing and processing his iconic images.

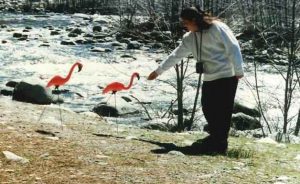

But I had something Ansel never could have imagined—two plastic, pink flamingos, purchased at the Armstrong Garden Center and placed with care on top of the luggage in the car trunk. If his work was iconic, I would go the other way—iconoclastic. My photographs would juxtapose the park’s natural splendor with crass, mass-produced symbols of the tasteless. I would become the “anti-Ansel” of Yosemite—my David to his Goliath. Watch out, Ansel. The battle had been joined.

The day of reckoning arrived. We parked near a breathtaking meadow with sparkling waterfalls in the distance. I opened the trunk, lifted out the birds and marched to a location that would provide the perfect scene—plastic, pink flamingos in the foreground accompanied by lush green fields and splashing cascades in the background.

Fellow tourists watched with interest, pointing and murmuring.

“Dad, do you have to?” asked my young daughter as I shoved the iron rod bird legs into the ground. The whine in her voice made clear she didn’t want us singled out for attention.

“I have to do this, Andrea. It’s a new concept. Bear with me.”

When we moved on to Half Dome, she said, “Dad, not again.” After Yosemite Falls and El Capitan, she surrendered to the inevitable.

The next day, while setting up flamingo shots, I noticed something which escaped me the day before—something miraculous. After I positioned the flamingos and opened the legs of the flimsy aluminum tripod holding my Canon AE-1, I observed people laughing and grinning. Eureka! I understood. They entered my world. The image existed in their mind’s eye, even before I snapped the shutter. The unprocessed Kodachrome film had not yet produced a single print—yet they enjoyed the composition as if it were printed on paper and set before them.

My bold attempt to outmaneuver Ansel produced an unexpected breakthrough. I had bridged the chasm between two worlds, photography and art. I had stumbled into becoming the first impressionist photographer. The suggestion of my vision created the finished impression in the viewer’s mind. Claude Monet and I were now soul brothers.

I declared a truce in my contest with Ansel. He still reigned as the master photographer of Yosemite. But I gained a new status in the struggle—the pioneering iconoclast, impressionist photographer of Yosemite.

On our last day, we ventured up to Tioga Pass, nine-thousand feet above sea level.

After parking the car, I set up the two flamingos in a snow bank. As I prepared to shoot, a bus filled with Japanese tourists came to a halt. Almost in unison, they lowered their windows, pointed their cameras and clicked away. A once-in-a-lifetime scene appeared before them—pink flamingos in the snow. The folks at home would never believe this.

When I reflect upon that magical time, I like to think the images of plastic, pink flamingos in Yosemite exist in the minds of those still living who bore witness.

As for the Japanese tourists who stopped on Tioga Pass that day, long-forgotten fading Fujifilm prints, languishing in boxes on closet shelves, testify to the reality of their experience—but not to the truth. Imagination interfered with realism.

“Lying,” as Oscar Wilde wrote in his essay, Decay of Lying, “the telling of beautiful untrue things is the proper aim of Art.”

Ansel, my nature-loving hero, each of us told untruths—you, in the darkroom, I, in contrasting the absurdly artificial with the pristine. No doubt your photographs are awe-inspiring. But who’s getting the laughs?